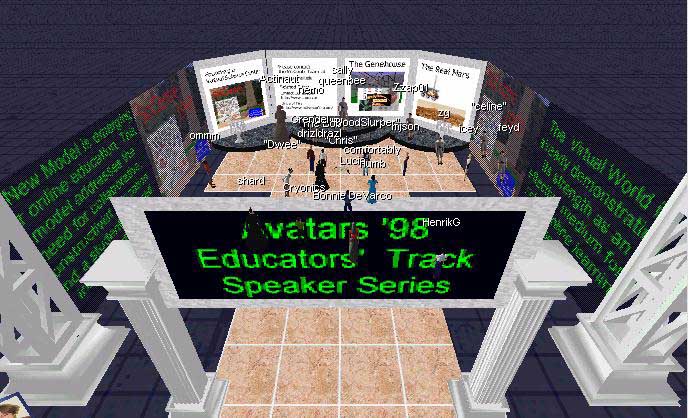

View of attendees standing at the ‘Ground Zero’

at the Avatars98 conference and tradeshow

Virtual Organizations and Virtual Worlds

A Case Study of AVATARS98

|

Bruce Damer & Stuart Gold Contact Consortium 343 Soquel Ave, Suite 70 Santa Cruz CA 95062-2305 USA |

Jan de Bruin & Dirk-Jan de Bruin Tilburg University/Virtual World Consortium P.O. Box 90153 5000 LE Tilburg The Netherlands |

View of attendees standing at the ‘Ground Zero’

at the Avatars98 conference and tradeshow

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE

A paper with Bruce Damer, Stuart Gold, and Jan and Dirk-Jan de Bruin on "Steps toward Learning in Virtual World Cyberspace: TheU Virtual University and the BOWorld" (April-May 1999). This paper is included in the printed proceedings of TWLT15: * A. Nijholt, Olaf Donk and Betse van Dijk (eds.), The Fifteenth Twente Workshop of Language Technology, May 19-21, 1999, Enschede, The Netherlands. This paper is published in Anton Nijholt, Olaf Donk and Betse van Dijk (eds.), Interactions in Virtual Worlds, Proceedings Twente Workshop on Language Technology (TWLT) 15, Universiteit Twente, Faculteit Informatica, 1999: pp. 31-41 (ISSN 0929-0672).

ABSTRACT

The paper explores the links between social movements, virtual organizations and Virtual Worlds. In order to be successful, social movements need organizations to give them direction. There is a fast-growing movement of dedicated Internet users who want to colonize Cyberspace and transform it into a galaxy of interconnected Inhabited Virtual Worlds (IVW). The Contact Consortium (CCON) is one of the spearheads of that movement. Because there is not a utilitarian or power relationship between the movement and the organizations, it is only possible to give the movement direction if one can mobilize consensus and commitment. This type of organization was called 'normative' in organization science (Etzioni, 1968: 104), and would now be labeled ‘virtual’ or ‘imaginary’ (Hedberg et al., 1997). Because commitment and consensus are so important, it is vital that these organizations create, maintain and expand them. Large-scale events that inspire and mobilize the adherents are essential. For CCON, the annual conference fulfills this function. Because the people involved in CCON are spread all over the world, its last conference – and tradeshow – was held in Cyberspace. This paper describes this new application of the medium IVW. Furthermore, we compare this type of virtual meeting with others of its kind. The thought behind the comparison is that different technologies, which emerge in different social contexts, will tend to converge. After summarizing our experiences with this new use of the medium IVW, we argue in the closing section of the paper for inclusion of Groupware in Virtual World browsers. To make Virtual Worlds real ‘worlds’ in the philosophical sense, social technologies, which facilitate deliberation and even policymaking, should also be part of virtual life.

Keywords: virtual organizations, inhabited or social Virtual Worlds, virtual conferences, virtual meetings, virtual teams, Groupware, Group Systems, Group decision support systems, computer-supported co-operative work.

1. VIRTUAL ORGANIZATIONS AND THE IVW MOVEMENT

Virtual or imaginary organizations utilize an inspiring vision, information technology, alliances, and other types of networks to initiate and sustain a boundary-transcending activity (Hedberg et al., 1997: 14). This type of organization can therefore act as the organizational arms of a movement or collectivity. The imaginary organization is based on integrative forces other than force and utilitarian motives (money) alone. Trust, synergy, and information technology are high on the list of those forces. With only a small core of employees, the imaginary organization can have an impact far greater than you might expect from its formal size, because of these characteristics and the trust developed by the many individuals involved. Organizations can become imaginary, or virtual, by a kind of transformation; Contact Consortium (CCON) started in this way. As a virtual organization, CCON has always depended heavily on the cooperation of volunteers.

For a virtual organization that is as dependent on its boundary-transcending activities and the efforts of volunteers as CCON, it is very important to organize large-scale events that generate commitment and consensus. These events should reinforce the vision, maintain old bonds and create new ones, exchange information and make the culture once more part of the collective memory of the movement. The annual conferences of Contact Consortium serve these functions. In 1998, CCON introduced two new elements: a conference and a tradeshow, which were entirely held in a universe of interconnected Virtual Worlds. The first element is very convenient for the participants of the IVW movements who are dispersed all over the world.

CCON wants to colonize Cyberspace by creating Inhabited Virtual Worlds. The real test is: can you create sustainable societies where complex social interactions, like ‘holding a conference’, ‘organizing a tradeshow’, ‘organizing a architectural competition’ (Damer, et al., 1999), are possible with a full range of social institutions to shape those interactions? Only then can the traditional philosophical concept of ‘world’ as an all-encompassing context for the totality of human activities and experiences be taken seriously (Düsing, 1986). CCON’s activities are focused on a variety of institution-building activities and, in doing so, they take the concept of ‘world’ very seriously. We will return to this topic in point 6.

The growing galaxy of interconnected IVWs is a new social reality. In point 2, we give a short overview of the history of IVWs as a new medium, and the different social contexts that were important in shaping them. There are, however, different technological media, often connected with different social contexts, in which all kinds of cross-fertilization occur. In this paper, we focus on virtual or digital meetings within the different media and associated social contexts. Such meetings can take place in chat rooms or boxes in the realm of pastime, in virtual classrooms in long distance learning, in the Electronic Meeting Room (EMR) of business organizations or Government agencies, or, as described in this paper, in IVWs. Convergence and merging between the various forms of ICT in different social contexts is the topic of point 3. The central question is: can IVW add something to the other concepts of digital, virtual or electronic meetings? In order to answer that question, we look at the AVATARS 98 conference in point 4: the focus of this paper. Because a paper is, however, a rather poor substitute for the real experience of graphical, multi-user IVWs, we shall demonstrate various IVWs in our presentation. In addition, we illustrate, by means of screenshots and photos in the appendix, the basic elements of a virtual meeting in IVW. In point 5 we summarize the experiences of this particular type of virtual (mass) meeting in IVW. In point 6 we speculate on the future of IVW and argue for the inclusion of social technologies in the form of Groupware in the IVW browsers.

2. A SHORT HISTORY OF INHABITED VIRTUAL WORLDS

Virtual community finds its technological roots in the earliest text-based multi-user environments. In the 1970s and '80s we saw the development of UseNET, LISTSERVs, MUDs, MOOs, IRC and conferencing systems like the WELL (Rheingold, 1993), and in the ’90s this continued on the World Wide Web. The merging of text-based chat channels with a visual interface in which users were represented as ‘avatars’ first occurred in Habitat in the mid-1980s (Benedikt, 1991) and reached an important milestone with the launch of the 3D Internet-based Worlds Chat in the spring of 1995.

VR-systems did not primarily influence the growth of online IVWs. We attribute their growth more to the fact that they built on their roots in MUDs and text-based real-time chat systems. Existing 3D-rendering engines, originally developed for gaming applications, provided the graphical component. Furthermore, the type of online IVWs that spread over the Internet, could run effectively on a large range of consumer computing platforms at modem speeds. To summary our position, the impetus for the fast growth of online IVWs comes mostly from the realms of pastime (chat systems and protocols) and games (rendering engines) and not so much from VR-systems.

The technology involved in serving up an IVW experience is extensive and impressive: for example, from client-server architectures, to 3D object models, to tricks dealing with latency, to citizen authorization and crowd control, and finally to databases managing, and mirroring hundreds of millions of objects and thousands of users across networks at modem dial-up speeds. An impressive example is AlphaWorld, which started in the summer of 1995. Currently, over 50 million objects occupy AlphaWorld, which can be visited by users with ordinary consumer computers. The literature surrounding Virtual World architectures, community development (Damer, 1995, 1996, 1998; Powers, 1997) and avatar design (Wilcox, 1998) is comprehensive and growing, so we will not address these topics further here.

IVWs are, as a medium, still in their infancy. At the July 1998 Avatar conference, consensus emerged that it was too early to know how the medium would ultimately be used. Avatar Cyberspace should continue to evolve for its own sake and not to serve possibly inappropriate applications. Virtual Worlds fall currently into three categories: multi-million dollar efforts in multi-player entertainment, smaller social and creative spaces supported as research efforts or home-brewed digital spaces by die-hard builders. The last category can increase enormously. The present generation is used to the document-based web. The next generation, brought up on Doom and Quake, is used to environments that stress navigation through very complex, 3D spaces full of behaviors. Will that generation bring us more into Virtual Worlds for play, learning, work, and just being? In ten years will Cyberspace look like Gibson’s Matrix or Stevenson’s Metaverse (Gibson, 1984, Stephenson, 1992), or will the document-based web and streaming video and audio spaces be the dominant paradigm?

3. THE CONVERGENCE OF TECHNOLOGIES AND THE CROSSOVER BETWEEN SOCIAL CONTEXTS

Predicting the development of technologies is difficult, if not impossible. However some tendencies can be applied. A familiar hypothesis is that technologies initially emerge and develop independent of each other, but eventually merge: The technological islands form a mainland or at least a peninsula. This also applies to the technological developments within the field of Information and Communication Technology (ICT). In ICT literature, the concept of ‘convergence’ is so often used to describe actual developments, that a journal on new media technologies, which started in 1995, chose the name ‘Convergence’. We pointed already to examples of crossovers between the realms of chat and gaming and the realm of IVWs. The next logical step is to see if the idea of conferencing and collaborative teamwork in IVW will eventually merge with the technological solutions being developed in the realm of business and government.

In the 1970s, we saw the development and experimental application of a variety of new social technologies to cope with the complexities of steering and policy processes in business and government, such as Delphi, Brainstorming, Scenario Writing and so on. Lots of these social technologies originated in new advisory organizations such as Rand and were further developed by the emerging policy sciences (Dror, 1971a and b). These social technologies didn’t change the traditional types of communication all at once. Today brainstorming is still mostly done in a room with people talking face-to-face. The basic assumption in conferencing is that face-to-face interaction is the richest form of communication for which computer-mediated communication is only a poor substitute.

Those social technologies were soon transformed into software (Groupware). Brainstorming, multi-criteria evaluation, voting, interviewing with questionnaires, measuring opinions, mind mapping and so on, can nowadays all be done in a computer-aided way. A whole new field of research emerged where the traditionally employed social technologies, such as brainstorming, are compared with computer supported ones (Petrovic & Krickl, 1994). These computer-supported social technologies eventually appeared in package form. The functionality of those clusters of computer programs is aptly expressed in descriptions such as Group Decision Support Systems (GDSS). The metaphor of a meeting in a room created the well-known concept of the Electronic Meeting Room (EMR).

EMRs were erected all over the world by using a local access network of computers powered by Groupware. In these meetings, people were still physically in the same room at the same time and place. The traditional face-to-face talks were then supplemented by computer-aided communication. By using notebooks etc., a mobile EMR can be created. For a couple of years now, Tilburg University has employed a mobile EMR using the Group Systems software (Smits et al., 1998). You can concentrate on improving the software, or try to improve the relation between the bundle of software programs and complex social processes such as (participatory) policymaking (Bongers et al., 1998, De Bruin & Van Harberden, 1999). Older versions of these software bundles were rather weak on graphical applications and not primarily designed with the Internet in mind. A meeting in this type of EMR is not really a very rich multimedia event.

The flexibility of computer-supported co-operative work is extremely enhanced when we move to web-moderated communication. ‘Virtual teams’, people working together via electronic networks, are an example. In a world in which globalization is supposed to be a trend, we even encounter expressions like ‘global teams’ defined as ‘a temporary, culturally diverse, geographically dispersed, electronically communicating work group' (Jarvenpaa et al., 1998: 3). If virtual organizations grow, these virtual teams will increase in importance. In point 1 we described trust as an all-important prerequisite for virtual organizations. Trust is necessary to cope with complexity and reduce the social control to implement a certain task. In discussing trust in virtual teams, types of ‘media richness’, forms of ‘social presence and identification’, and ‘types of action’ need to be addressed. Can we, for instance, apply Meyerson’s ‘theory of swift trust’ in temporary teams such as filmcrews, theater and architectural groups, to virtual teams preparing an event in IVW as described in point 4? According to Meyerson, ‘highly active, proactive, enthusiastic, generative style of action’ (Meyerson et al, 1996: 180) is productive in maintaining trust.

This type of collaborative, computer-moderated work can be done using various technologies. Electronic mail technology and chat room technology are still the most frequently used. The trend is, however, towards rich multimedia digital conferencing on the Internet. Various prototypes are being produced at this very moment. The intension is to ‘marry the user-friendliness and pervasiveness of Web-based multimedia browser interfaces with on-line interaction and collaboration, using text, graphics, and voice communications.’ (Bisdikian et al., 1998: 282). However, this approach is still about interfaces; users don't feel like they're in a place.

In point 4 below, we present a picture of a web-enabled multimedia teleconferencing system, set within a string of connected places, viz. various Inhabited Virtual Worlds. Our description does not bother to consider the developments described above. These are discussed in point 6. After summarizing our experiences with Avatars98 in point 5, we return to the topic raised in point 3: life in IVW should also take into account the complex organizational and policymaking tasks and make use of the relevant social technologies and bundles of groupware which have been developed for those purposes.

4. AVATARS98: CONFERENCE AND TRADESHOW INSIDE INHABITED VIRTUAL WORLDS

4.1 BACKGROUND BEHIND THE EVENT

Avatars98 was produced by DigitalSpace Corporation (www.digitalspace.com) for the Contact Consortium, which is a global forum on the development of IVW Cyberspace. The Avatars98 conference was the third in a series of annual conferences hosted by the Contact Consortium and its corporate, institutional and individual membership. The first two events were held in traditional facilities in San Francisco in 1996 and 1997. It was decided to put the medium of Inhabited Virtual Worlds to the test and hold the entire conference online in 1998.

On November 21, 1998, the Contact Consortium (www.ccon.org) hosted the world's first conference and tradeshow inside cyberspace. It allowed several hundred organizations to connect synchronously with each other and the attendees. By ‘inside cyberspace’ we mean that the main interaction of the conference was carried out within 3D Virtual Worlds on the Internet. Unlike other models of ‘cyber-conferences’, this event did not simple broadcast events happening at one location to another, but instead moved the main interaction into one shared cognitive Cyberspace inhabited in real-time by attendees represented as ‘avatars’.

The conference hosted over 4,000 attendees in a 3D online Virtual World, with 6 speaking tracks of 50 speakers presenting sessions to a freeform net connecting the audience, an exhibit hall representing 48 participating groups, an art show, parallel webcasts, and 40 globally connected locations.

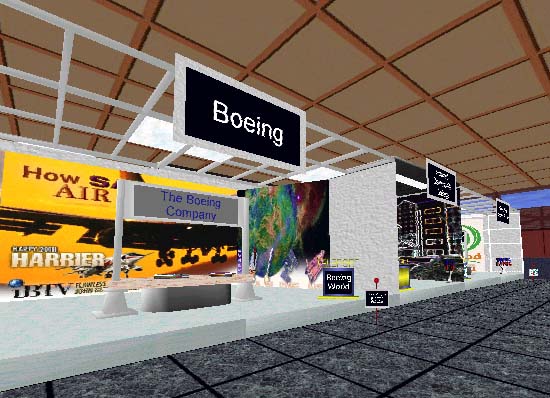

Exhibits for companies and participating organizations such as Boeing

4.2 TECHNOLOGY PLATFORMS AND OPERATION

A number of Virtual World platforms, such as Active Worlds, Blaxxun, Traveler, WorldsAway and Roomancer, and several webcast technologies were used. The main focus was the ‘AV98' conference hall in the Active Worlds platform. The Avatars98 world was designed to be usable by attendees on low-end (Pentium 100) computers on minimal net connections (14.4 BPS speed modems).

The Active Worlds technology provides streaming and reuse of 3D objects in a Lego-like manner so the designers produced a series of components (struts, signs, potted plants) that were put together to make the conference hall. Avatars, animated 3D models of users, were also specially designed (some wearing conference t-shirts). Once these objects streamed into the cache of attendees' hard disks, rendering could be done locally.

Streaming webcasts were presented on some of the 3D surfaces to bridge some of the 40 physical locations into the virtual attendees within the world. Communication was carried out by text chat, which was also logged for the conference proceedings.

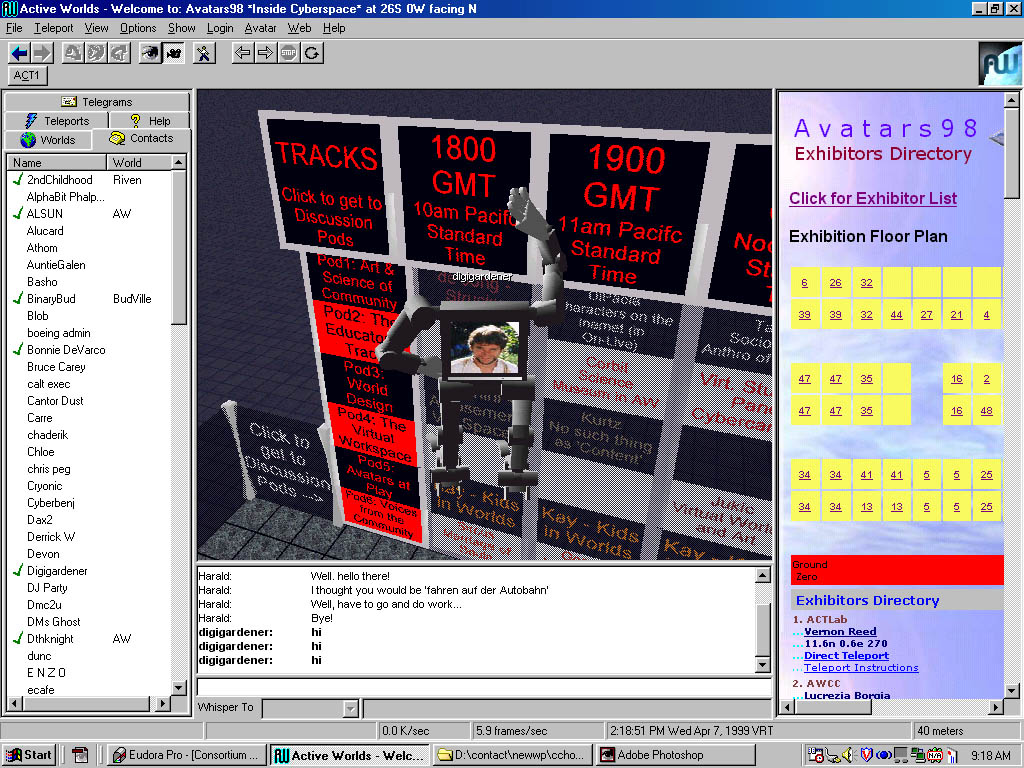

Active Worlds browser showing the 3D view with conference chair Bruce Damer waving in his custom avatar floating by the schedule board, chat window below, webpage showing the exhibit hall to the right and a list of active users on the left

4.3 VISITING THE AVATARS98 VIRTUAL WORLD

You can still visit this space by downloading and installing the browser from http://www.activeworlds.com/ and selecting the AV98 world. A full report on the event, including proceedings, is located at: http://www.ccon.org/conf98.

The AV98 world is a one-kilometer square space in which a conventional conference hall was constructed. DigitalSpace worked with dozens of volunteers, including the prime object and hall design team of Koolworlds (brothers Max and Dax from Vancouver Washington in the USA) under the guidance of DigitalSpace partner Stuart Gold, an architect from London.

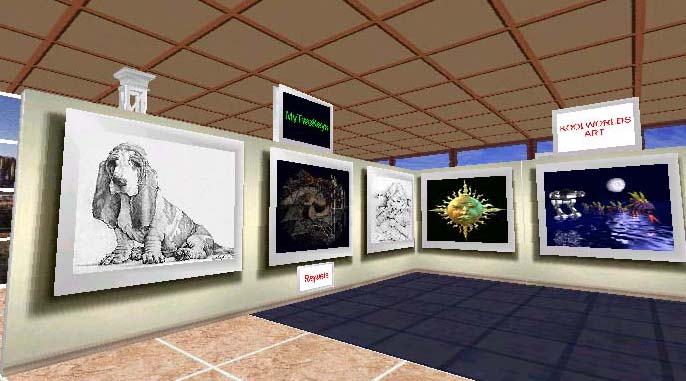

Art Gallery with streamed JPEG images from artists all over the web

The conference hall featured a ‘Ground Zero’ landing zone for new attendees, a series of 48 exhibits for participating companies and organizations, an art gallery, a webcam wall showing two dozen webcasts from participating locations, a ‘big board’ conference schedule, an awards area, and six ‘speaker pods’ for parallel tracks in virtual ‘breakout rooms’.

4.4 BEHIND THE SCENES AT THE AVATARS98 EDUCATORS’ TRACK

To give an impression of how the conference was conducted, we go briefly to one of the tracks. CCON has several Special Interest Groups (SIGs), each covering a certain topic. Several SIGs organized their own track. One of the more popular involved the relation between Virtual Worlds and learning. The Avatars98 Educators' Track was one of the best attended and best produced at the conference. Bonnie DeVarco, track coordinator, is currently preparing a report about the behind the scenes planning and operation of the track, which will discuss the following standard elements:

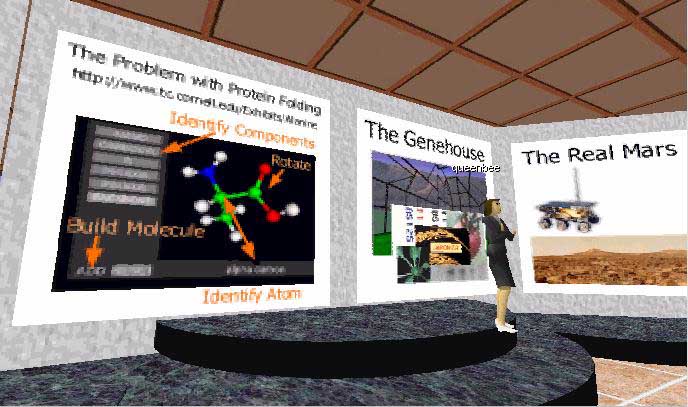

Presenter Margaret Corbit of the Cornell University Theory Center presenting in the ‘speaker pod’ to a collected audience of educators interested in the use of Virtual Worlds in the learning setting. Margaret's slides are being changed in real time by session coordinator Bonnie DeVarco

Session attendees in the ‘speaker pod’ at the Avatars98 conference

5. WHAT WAS LEARNED ABOUT CONFERENCING IN IVWs?

Highlights of the conference:

Things that could be improved:

In conclusion, while quite labor intensive, virtual conferences and tradeshows modeled after Avatars98 will produce wide coverage and easy access for large audiences. It can be packaged for a number of themes including a Cyberspace extension to existing ‘real world’ events, and some of the most interesting activities yet offered on the Internet. We expect events like this to be increasingly part of the online time of ordinary and business net users alike in Cyberspace.

6. THE FUTURE OF THE MEDIUM IVW

We opened our paper by observing that the further development of IVW of Avatar Worlds on the Internet is not easy to predict. With that in mind, we close this paper with some tentative observations, roughly using, Parsons’ theory of evolutionary universals (Parsons, 1966) to the evolution of IVWs:

If we look at the Special Interest Groups of CCON, this virtual organization is facilitating the breakthrough of IVWs from the primitive to the modern phase of societies. In the modern phase, IVWs need the social technologies associated with various functional subsystems of society. The integration of Groupware in the VW browsers would make them an even more exiting place to be, but would also make them more suitable, as an exercise ground, for the policy and organizational tasks of real life.

REFERENCES

Biographical Information

Bruce Damer and Stuart Gold are members of the Contact Consortium. Damer co-founded the organization in 1995 and Gold has headed up TheU Virtual University projects since 1996. Dr. Jan de Bruin is a policy scientist at Tilburg University, who is trained as an economist, sociologist, and political scientist. Dirk-Jan de Bruin is a member of Contact Consortium and founder of Multi-Users Virtual Worlds Consortium.

Appendix: Elements of a Virtual Meeting in an Inhabited Virtual World

Avatars

Avatars

Avatars are the visual embodiment of people in Cyberspace. Attendees at virtual meetings are all given a choice of avatars to represent them. They can be quite fanciful or down to earth. By using Avatars, you can go beyond simple conferencing in which (spoken) text and documents are exchanged. Avatars can, increasingly so, embody such important aspects of human communication as gestures, proximity to the group, and emotion.

The virtual worlds in which avatars can be used can be very powerful in supporting collaboration and complex work and learning processes. Virtual worlds are not merely transmissions of one real world place to another; they are new spaces that we enter, spaces that exist nowhere else but in Cyberspace. Virtual Worlds and Avatars are uniquely suited to support virtual meetings, from small gatherings up to cyber-tradeshows with thousands of attendees connecting in from all over the Earth.

Virtual Meeting Spaces

Private Auditorium Spaces Multisession Meeting Spaces Conference Center

There are as many styles and shapes of virtual meeting spaces as there are 'function spaces' in traditional settings. Three types are pictured here. The private auditorium, where 'one to many' presentations are done to usually closed audiences with the assistance of bot-driven slide shows or audio. The multisession meeting space, where a larger open attendance experiences a two way interaction with one or more speakers during a track of related topics, supported by web links, live video and audio streaming and backchannel chat for questions and answers. Lastly, the conference center, which hosts a pass through crowd usually on the way to more specific events or who are in need of help or directory assistance to the larger conference hall or current events.

Exhibitions

Booth Booking and Design Exhibit Hall

As in a physical tradeshow, virtual exhibitions permit a large number of organizations to present their wares, offerings or interesting content to a walk-by audience. Pictured here is a sampling of a 16 by 16 meter sized booth from the web-based booking page and completed booths by companies such as Boeing that appeared along one island in the Avatars98 conference hall. A person from the sponsoring organization can occupy booths (sometimes called 'stands') full or part-time. In some cases, bots (automated conversational agents) can be present in the booth and seek to get the attention of passers-by, present a number of simple options and answer questions, or drive the visitor's web-browser to retrive their conference pass information and perform a 'card swipe' operation in exchange for sending information or free gifts. Lastly, booths can serve as portals into either the organization's website or to custom built virtual worlds where special talks or events might be sponsored on the day of the conference

Crowd Flow and Management

Big board Schedule Attendee Flow and Management

As with large event spaces like a conference hall or theme park, giving people clear directions and updates is very important to them walking away with a coherent experience. One difference in a virtual conference space is that visitors can instantaneously 'teleport' or 'warp' from one location to another. This is akin to taking an elevator (an analog for teleportation, taking the visitor seemingly instantly from place to place) or an escalator (the more gradual and visible ways that visitors are moved usually within adjacent areas). Signage indicating short distance warping or longer distance teleportation between worlds must be consistent and act only at the visitor's request (usually by the click of a mouse). Innovations like the ones pictured here help to route visitors to larger event spaces: on the left is a 'big board' conference schedule, borrowed from Neal Stephenson's novel Snow Cras. This is a tall 3D billboard of events listed right to left in Greenwich Mean Time and local time while the top to bottom row indicates which multisession meeting space the event is occuring in. Clicking on any panel on the Big Board will warp the visitor to the appropriate space. On the right is an elevator shaft that routes visitors up or down floors in a cylindrical building full of meeting spaces and private auditoria constructed for a European health insurance company. One of many other interface affordances for crowd management is broadcast chat messages that will reach every attendee with updates, time announements and other key event milestones, with instructions on how to move to an announced location. Providing conference directory objects within view of every location in a conference hall gives visitors the option to click on a directory and access the parallel Web browser page for the event. Web pages will also have URL links, which can warp or teleport visitors within the worlds.

Extra Events

Art Gallery Multipoint Webcast

Extra events add more value to a larger cyberconference or tradeshow. Here we see two such events, including an art gallery permitting the public to submit 2D artworks or photographic images for display, or a 'webcasting wall' to display live camera views of a number of participating real-world locations or news broadcasts.

Live Webcasting

Live Broadcast Video and Audio Streaming

Web casting can provide streams of video and audio from real-world locations directly onto surfaces in the virtual world (seen here on the left is a CNN broadcast of returning astronaut John Glen in orbit in 1998) or onto parallel web pages (seen on the right). These mediacasts are often very important to create context for the event and can be featured in session spaces to stream speakers out to live 'in-avatar' audiences who may be talking back by text chat or shared voice channels.

Production Team and Physical Location Management

Team Room Setup Live Crowd Enthusiasm Integrated video and Crew and Show

virtual world broadcasting Control

Every virtual meeting will have some physical team locations, even if to merely coordinate the action in-world. The proper definition of roles, clearly posted information about schedule, group dynamics and a culture of respect and quality hosting, handling fatigue after hours at the keyboard, and providing interesting visuals by webcasting from the "operations center" all bring a virtual event to life. It has often been said that some of the presence of the "people behind the avatars" can be felt at well run events, and good team management and motivation at the physical locales is a key to producing this general feeling.

Back to Papers Index

(c); Copyright DigitalSpace

Corporation 1999, all rights reserved

Contact our webster

for comments on these pages